Dr. Kaustav Bakshi | 6th September 2023

QAMRA remembers the contributions of iconic filmmaker Rituparno Ghosh in the tenth year of his passing, through this thoughtful reading of his films by Kaustav Bakshi.

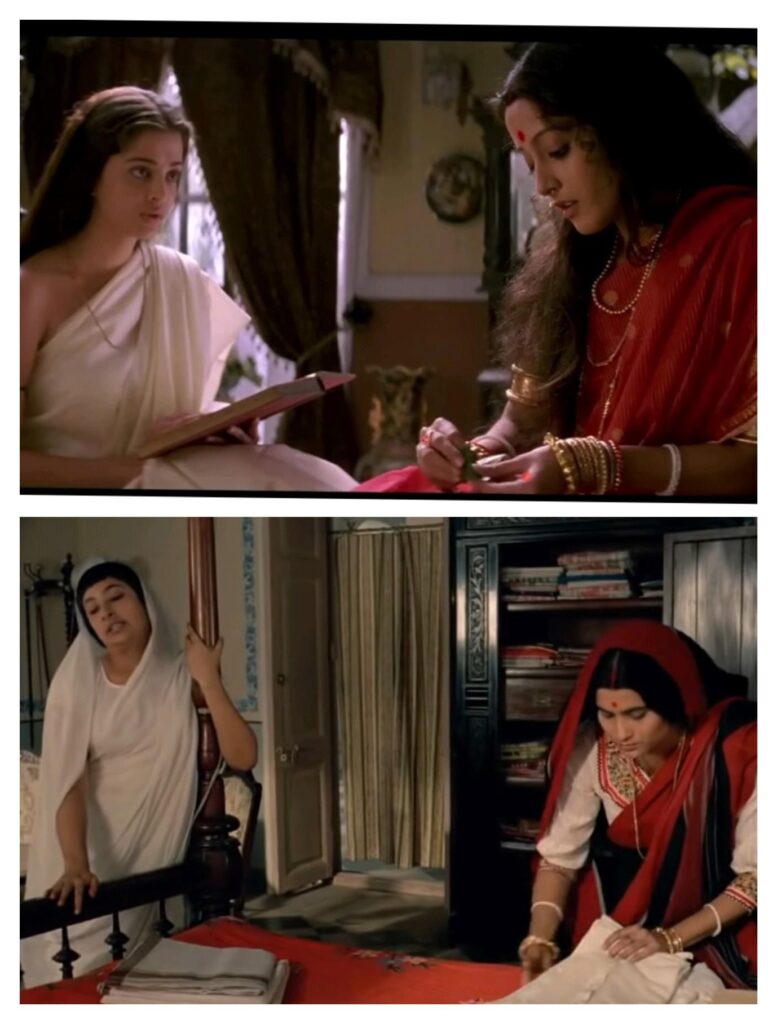

In filmmaker Rituparno Ghosh’s (1963-2013) Noukadubi, a couple, separated from their legitimate spouses after a boat wreck immediately after their arranged marriages, cohabits without realizing they are actually married to different people. Noukadubi/Boat-wreck (2011) revolves around mistaken identities, heartbreak, and mismatched couples, and is based on Rabindranath Tagore’s novel of the same title. The plot unfolds largely through chance and coincidence. Though not among Tagore’s most acclaimed works, the novel remains popular; it is intense yet light, sentimental yet suspenseful – in other words, quite suitable for cinematic adaptation. Rituparno introduced Rabindranath as an absent-present character in this adaptation, which appealed to those interested in late 19th and early 20th century Bengali high culture.

I begin this article with reference to Noukadubi to show how Rituparno played with the trope of (mistaken) identities in the cinematic medium to express his gender-queerness, even when he did not explicitly ‘come out.’

My Friendship with Rituparno

Between 2007 and 2016, I maintained a blog on cinema, often writing elaborate reviews of regional films. My friendship with Rituparno Ghosh grew out of that blog. In 2010, the release of Kaushik Ganguly’s Arekti Premer Golpo/Just Another Love Story created quite a stir in Kolkata’s LGBITQ+ community; Rituparno debuted as a cross-dressing film-maker in love with a bisexual man (essayed by Indranil Sengupta). Indranil saw my review on Facebook and forwarded it to Rituparno, who called me immediately. We spoke for hours, and that conversation cemented our friendship. A fan boy for years, I would imagine conversations with Rituparno, but didn’t think I would see the day. By 2010, Rituparno had become a household name, and for us, queer folx of Kolkata, he was an icon and anchor. I visited him at least twice a week, we shared numerous adda sessions, and socialized with him often. A phone call at 6 am meant it was none other than Ritu-da (as we all lovingly called him); he would joke that I was the only person available for emotional palavers so early in the morning. Ritu-da followed my blog, and, apart from when he was shooting, we spoke regularly about cinema, literature and the arts, our identities as queer individuals, relationships, our community, fears, and everything else under the sun.

Probing the trope of mistaken identities

Just as I did with Arekti Premer Golpo, I wrote a review of Noukadubi. It focused on Rituparno’s intra- and intertextual dialogue with Tagore within the cinematic text. Rituparno felt that I had overlooked an important subtext, drawn from the famous Bhawal Sanyasi case (1936-1942). The film Sanyasi Raja/The Hermit King (1975) featuring the Bengali matinee idol Uttam Kumar in the title role had record running at the box-office, and had been on Rituparno’s mind.

Sanyasi Raja remains alive in the memory of Bengali cinephiles, and several adaptations of the original have been made of late, catering to the nostalgia Bengalis have for the film. Rituparno found it unjust that I did not reflect on the Sanyasi Raja subtext, as I had on Tagore, for his cinema was as much a product of commercial cinematic traditions in India, as it was of Bengali high intellectual culture. While not formally trained in filmmaking, Rituparno’s cinema betrays his debt to critically acclaimed filmmakers including Satyajit Ray, Tapan Sinha, Guru Dutt, Aparna Sen as well as hardcore commercial filmmakers such as Vijay Anand, Raj Kapoor, Yash Chopra, Tarun Majumder, Ajay Kar and others (see my interview with Rituparno, published in 2013). Rituparno, therefore, held immense appeal for a range of audiences in Bengal, who found in his films a familiar cinematic language. A close look at his films reveals how he played skillfully with images and frames from Guru Dutt’s Kagaz ke Phool (in Abohoman), Vijay Anand’s Guide (in Chitrangada), Satyajit Ray’s Charulata (in Badiwali) and Ghare Baire (in Chokher Bali), Tarun Majumder’s Khelar Putul (in Noukadubi), and so on.

Returning to the Sanyasi Raja subtext: the film was inspired by the Bhawal Sanyasi case in which a popular prince of the Bhawal zamindar Estate, in modern-day Bangladesh, died away from home under mysterious circumstances. Some years later, a sanyasi arrived in Bhawal claiming to be the dead prince. His remarkable likeness to the prince, and his familiarity with the prince’s personal life led to a legal battle in one of the most electrifying court cases of the colonial period.

This court case, revolving around questions of authenticity, acquires meaning in Rituparno Ghosh’s cinema, for he played constantly with his identity on screen, even when not making an explicitly queer film. Long before he came out, Rituparno used the film medium to play with his androgynous self. One may contend that most of his films are queer, with ambiguous identities, suspicion, revelation of real identities being compelling tropes. Noukadubi, premised on Sanyasi Raja, is not overtly queer, but a subtle and layered engagement with the question of ‘real’ identities coupled with the tragicomic implications of mismatched couples. In retrospect, films such as Asukh (Malaise), Badiwali (The Lady of the House), Chokher Bali (Passion Play), or Raincoat appear to be telling us a queer tale in the heteronormative garb of love, loss, separation and sexual desires.

Queer Imaginings

Rituparno’s queer cinematic sensibility does not have the volatility of a Pedro Almodóvar or the boldness of a Peter Cattaneo. He moved cautiously in his films, where queerness is all too familiar, recognizable, every day, nothing out of the ordinary. Yet, the extraordinariness of it! He began his experiments with Chitrangada: A Crowning Wish, a well-known dance drama by Rabindranath Tagore with which most Bengalis are familiar. Chitrangada is perhaps Rituparno’s most experimental queer film, although with familiar signposts. Moving seamlessly between real and surreal time and space, the film seems to inhabit an in-betweenness – a metaphor of the male protagonist’s desire to transition to a woman. The Tagore subtext adds to this cinematic ploy. Tagore’s Chitrangada, based on an episode from the Mahabharata, vouches for the beauty of the soul over the beauty of the body, the latter being temporal and therefore undesirable. The dance-drama opened with the following prologue:

Manipur Raj er bhakti te tushto hoye, Shib bor dilen je raajbongshe sudhumatro putroi janmabe. Totsatweo, jokhon rajkul e Chitrangada r janmo holo, Raja takey putro roop e palon korte thaklen…

(Pleased with the devotion of the King of Manipur, Lord Shiva granted him the boon that the royal family would only bear male children. In spite of this, when Chitrangada was born to the royal family, the King brought her up like a son…)

The two phrases “in spite of this” and “like a son” are important – what we infer from this little back story is this:

Rituparno Ghosh’s film takes off from these inferences. Smitten by Arjun, Chitrangada approaches Madan, the God of Love, to bestow upon her feminine grace and beauty for a year, so that Arjun falls in love with her. Though Madan grants her the boon, she returns the boon before the year ends, unconvinced by the superfluity of bodily beauty. Perhaps, the most recognizable literal link between Tagore’s text and Ghosh’s film lies here: Rudra, the protagonist of the film, too calls off his reassignment surgery, realizing it is not worth changing oneself for the sake of a man. The film not only opened up Tagore’s 1892 text to queer interpretations, it also gave Bengali cinema its first trans-queer protagonist who made the agony of gender assignment surgery emotionally intelligible to a largely uninitiated audience.

Rituparno prepared his audience for nearly 20 years before making queer sexualities a subject of his films. My growing friendship with Rituparno gave me more insight into his creative processes. One day, while discussing Asukh (1999), his third film, I heard his own story and the emotional turbulence he felt, via the story of a lonely film star and her cloistered world of parents, an untrustworthy boyfriend and Rabindranath Tagore’s poems and songs. Who knew Asukh was an autobiographical film? Returning home, I watched it again. It occurred to me that much of the film is set within a closet-like space – a dimly lit room, with no access to the outside world, except for a half-closed door. The protagonist’s suffocation within the space was almost palpable.

The same ‘closet-like feel’ returns in both Badiwali (1999) and Raincoat (2004): while Badiwali’s opening credits roll over a closed door, the emotional drama of Raincoat unfolds in a closed room cramped with furniture. In Rituparno’s house too, there was one such room that was a furniture dump with props used in films – mostly props used in films. In Raincoat, he recreated that room in which two lovers meet after years, who know they will never reunite. A telling metaphor of queer separations and the impossibility of legitimate coupledom, Raincoat is a queer film in disguise, articulated visually through the feeling of suffocation.

In Badiwali, Ghosh’s queerness articulates itself in Prasanna, the older servant of the house. Apart from that, the film follows Banalata’s confinement in a decaying mansion, her detachment and repressed sexual desires and her eventual abandonment by the man she loves. The closing frame depicts an empty bed as the title sequence rolls.

It is interesting to note in this context that Riutparno also lent his voice to female characters, when he was dissatisfied with the dubbing. In Noukadubi, he dubbed for Ammu Chatterjee who plays Nalikansha’s mother in the film; in Chokher Bali, he dubbed for a middle-aged woman who brings a marriage proposal for Bihari. When Rituparno eventually came out, all his previous works acquired a queer currency in hindsight.

Rituparno once told me, “My activism is in my work. I do not need to walk the Pride.” As a cultural activist, he knew how to mobilize his audiences in support of a cause. For Rituparno, it was not only a ‘cause’, it was a question of survival. What is a filmmaker without a loyal audience? In interviews I’ve undertaken, several queer folx from Kolkata revealed how they felt a sense of belonging in Rituparno’s films, at a time when popular culture barely had queer representations. The long and short of it is this: in his attempt to de-normativize Indian cinema, Rituparno worked within its tropes and traditions, taking his loyal audiences along, and they gradually began to look upon queerness as ordinary. More enthralling is how a queer filmmaker used the audio-visual medium of cinema to perform his queerness for several years, while he gathered courage to come out.

Note: Rituparno passed away before gender-neutrality and pronoun-consciousness became popular. Rituparno preferred ‘he’, for there were few choices. However, in my book, I used zie, hir, etc for political correctness. Here I chose to stick to the masculine pronoun, for I thought what’s the point, if Rituparno himself was never wary of his pronouns.

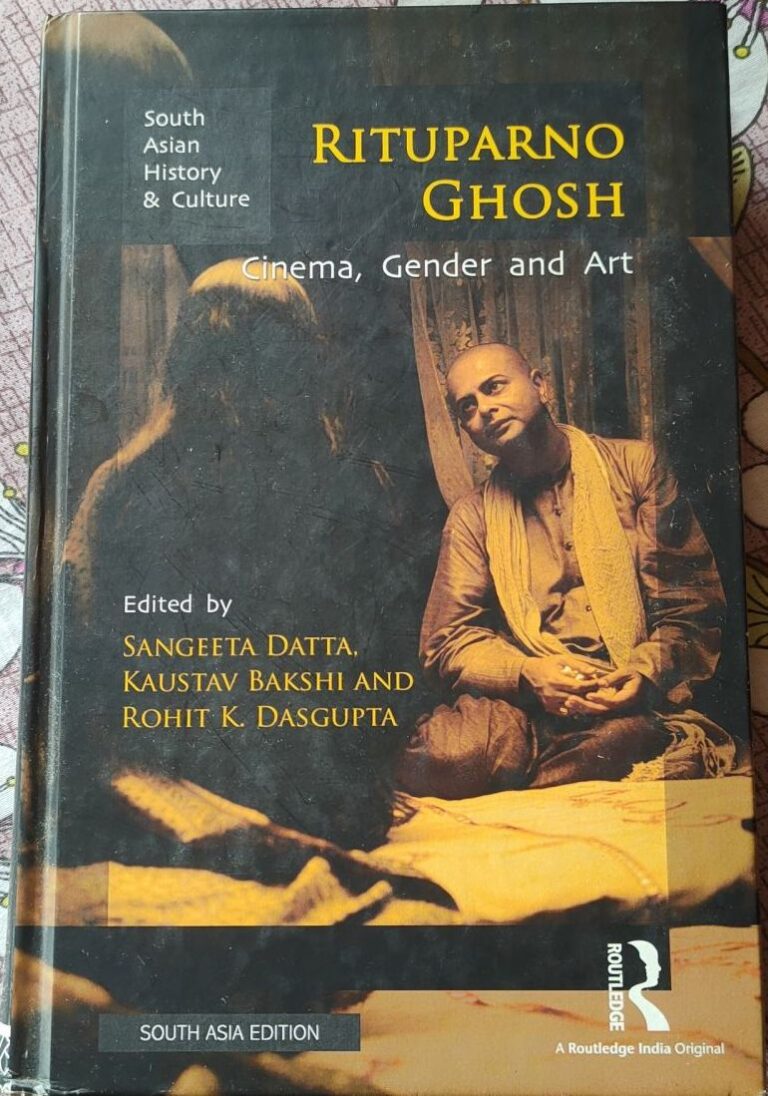

Dr. Kaustav Bakshi is Associate Professor, Department of English, Jadavpur University. He has co-edited Rituparno Ghosh: Cinema, Gender and Art (Routledge, 2015), and Queer Studies: Texts, Contexts, Praxis (Orient Blackswan, 2019), among other works.