QAMRA | 6th June 2023

The QAMRA Archival Project is concerned with the nature of record-keeping in postcolonial India. Records in the postcolonial state archives from the 1980s onward will determine what future historians will base their studies on for this time period. Anticipating a dearth of rich documentation in the state archives, we wish to think about what records independent archives might keep, bearing in mind historiographical turns since the 1960s including the cultural turn, everyday history, the ecological turn, queer-trans-feminist interventions, or science and technology studies.

To explore these archival concerns, QAMRA and the Centre for Labour Studies, NLSIU, hosted a discussion with Profs. Janaki Nair, Kamala Sankaran and Babu Mathew on documenting working lives on 2 May 2023. Each was asked to speak of their scholarship on labour in the context of their personal journeys in/with labour movements. We were delighted to see a full-house at this campus event, with many old-timers in the labour movement turning up that evening to listen to their comrades.

Prof. Janaki Nair retired as historian at JNU, and her path-breaking and methodologically innovative works include Miners and Millhands (1998), The Promise of the Metropolis (2005), Mysore Modern (2011). Prof. Nair presented the different ways in which historians of labour have gone beyond studying collective action and the workplace.

Prof. Kamala Sankaran is Chair Professor at NLSIU and her works include Freedom of Association in India and International Labour Standards (2009), Challenging the Legal Boundaries of Work Regulation (2012) and Affirmative Action: A View from the Global South (2014). Prof. Sankaran introduced the audience to leaders of various trade unions, whom she had interviewed decades ago. She also spoke of the different archives she had accessed for her labour research.

Prof. Babu Mathew is former Registrar and faculty at NLSIU. He was Country Director of ActionAid International in India. He has been closely involved in collective bargaining processes at both national and local level, as chief negotiator on behalf of workers. He was also Vice- President of Trade Union International for two terms. Prof. Mathew shared his experiences, as a lawyer and trade unionist, in the public sector and private sector industries.

This event was dedicated to the memory of historian Ranajit Guha (1923-2023), who, with a younger generation of scholars, developed a remarkable new reading of the colonial archive that came to be called Subaltern Studies. He exhorted us, in the essay Chandra’s Death, to bend to the ground and take seriously the fragmentary record which comes to us without context.

Given the rich discussion, and potential suggested for further research, QAMRA has made available a lightly edited, complete transcript of the event below.

(I will not refer to the images by Birendra Kumar Yadav, Sreeja Pallam and Balaji Ponna, but I wanted you to have a sense of how labour issues have inspired artists. I am going to speak, as I have been asked to, about the relationship between labour and the archive.)

Beginnings in Journalism

I will be autobiographical to start with, in order to say that this interest in labour, and labour history, came out of my experience as a journalist, who had the freedom – a freedom that no longer exists – of reporting on working class struggles. Believe me, there was a moment – in the 1980s – when it was possible to write on labour issues, and newspapers and journals would actually carry those articles. I used to even write for Business India, imagine that.

Of course, the newspaper is one of the most useful archives. And when you look at the archives, for example, of The Hindu newspaper, which is more than a hundred years old, there was regular reporting of labour issues, and particularly of labour protest.

Labour History in the 1980s: Collective Action and Protest

I sort of segued from being a journalist in many things – also labour – to wanting to do something more substantial, and moved into History, and labour history in particular. The interest [at that time] was in collective action of the protest kind. It was an attempt to look at an archive from the perspective of, ‘What are these moments of collective action which are protests?’ ‘What is this historic struggle between capital and labour?’ And of course, our interest was so narrow, one was looking at the archive only from the point of view of ‘What were these protests? How frequent were they? How long were they? How were they organised? Who participated?’

Changes in Historiography

We began to realise, as historians, that collective action is not the whole story. The story of labour spills well beyond the actions that they may undertake collectively, especially because you realise, when you study working class action from as early as 1893, that very quickly these working-class actions deteriorate into riots. And these riots were quite serious. So, in Bombay and Calcutta in 1893, you had inter-worker riots, between Hindu and Muslim workers.

So, what is it that inflects working class history, from the perspective of language, from the perspective of religion, from the perspective of ethnicity, and so on? These are questions that began to interest us from about the 1990s.

Ranajit Guha and Religion as Archive for Labour Studies

Now, it is appropriate that we are honouring Ranajit Guha. And one of the most important articles which I’ve found useful for my own work, is the one called the The Career of an Anti-God in Heaven and on Earth, in which he starts by saying, Religion is one of the richest archives in the Indian subcontinent. And the reason he says this is because everything to do with the working class does not necessarily leave an archival trace. This does not mean that the working class or labour was not present throughout history. Of course, they were present throughout history, but they don’t necessarily leave an archival trace in the form of, say, documentation. All of us were inspired by EP Thompson’s fabulous, almost thousand-page book, The Making of the English Working Class (1963), but Thompson had access to an archive that we can only dream about, because in his case, and here’s one of the big distinctions between, say, countries like England and countries like ours: We do not have levels of literacy to match those situations where workers represented themselves. We don’t have that situation in India, even today. So, we are reliant for much of our work on other sets of historical sources, and the biggest source provided to us is by the State, such as in the Departments of Industry and Labour, with their accounts of what happens.

But as Ranajit Guha told us, religion is one of the richest archives. How do we interpret, for example, religious practice at sites of labour? There may be no paper trail, as I said; it may be entirely dependent on us to conduct historical fieldwork – and I’m going to cite two people whose work has been extremely germinal to the understanding between religion and labour history, and they are June Nash and Michael Taussig, both of whom studied Latin America, and in particular Latin American mining and production of different kinds.

Social anthropologists rather than historians have richly documented this relationship between religion and work. As you know, the book that Taussig wrote is called The Devil and Commodity Fetishism in South America, in which he develops an argument about the pact between miners in Colombia and the devil, and the ways in which it ended up in degrees of self -exploitation. Those of you interested should engage with that book.

So, there are, in the Indian records, many traces of such negotiations between workers and employers, about, for example, the kinds of holidays that will be given for Ayudha puja, being a major marker in the calendar. How is religion used as a tactic to extract, as it were, certain concessions from employers from the State? There are interesting traces like that, that come to us from the archives as well.

Law as a Labour Archive

But I am in a law school. And one of the richest sources of labour history is also the law. I have here Megha Sharma who has studied state law and the ways in which it has shaped workers’ working lives – I’m going to come to workers’ non-working lives in just a minute. To look at the law, and not just the kinds of agitations that produced law that limited the freedoms of capital (for which the 19th century is the best example): In the mother of capitalist industry, which is England, you had the state being invited in by workers themselves, to limit the rights of capitalism to an endless working day. So, throughout the 19th century, there were battles for a shorter and shorter and shorter working day. The state actually does step in. So, the law becomes a very important instrument by which the workers are able to extract, as it were, some concessions from a laissez-faire State. Remember that the state did not actually limit capitalism in its early stages.

Today, we are in a very different moment. Here, the State – and my colleagues here including Geeta [Menon] will bear me out – is playing a different role in terms of enabling capital by extending hours of work, which is exactly the opposite of almost a century of struggle to limit the working day. We can come to that perhaps in discussion, but I’m just giving you a sense of the fact that the law and, in particular, case law becomes a very, very rich archive for understanding the collusion – the voluntary and the involuntary collusion – of workers with the state. Voluntary, for example, in the work that Megha [Sharma] has done in which workers actually go to court to obtain some of the rights that they have been bestowed, but the involuntary is also equally interesting. There are cases where mobs, for example, are investigated and you find quite a large number working class people who are members of mobs who might undertake certain kinds of actions, which are then investigated, and even penalised, and there you have a very rich source of social history, which is an unexpected or involuntary collusion, as it were, of these workers with the state.

Beyond the Workplace

If I can go back to my historical survey, by the 1990s, labour histories were looking beyond the workplace. And this became an important and necessary step to say that, especially, in the case of Indian workers, the neighbourhood played as important a role in shaping the experience of work as the place of work itself. And, of course, the pioneer in this was Rajnarayan Chandavarkar and his work on Bombay, but many others have since followed him. While working on my book on Bangalore [Promise of the Metropolis: Bangalore’s Twentieth Century (2005)], I was very struck by the fact that the planning documents for Bangalore of the 1950s and the 1960s paid a good deal of attention to the housing of the working class in Bangalore. You will not find it in contemporary planning documents. But it was certainly a preoccupation of the 1950s and 1960s. That’s how important the public sector was to the shaping of the city. And, that’s how important the public sector was in the imagination of planners of the city itself. So, there are very unexpected sources from which one gets a picture of non-working lives, you know, the kinds of questions that concern housing, neighbourhoods, education, celebration, and festivals, and so on – themes which engage labour historians worldwide.

The Question of Skills

Another theme for which we have very little by way of archival material – and we will have to think of ways in which we investigate this question – is the question of skill: How is skill built up in the workplace? What are the ways in which workers learn skills? We have a lot to learn from inherited skills, which come into the workplace, and that might be through the instruments of caste, or skills which are learned in completely new kinds of engagements, either in factories or mines.

I had reason to think about mining. And, in particular, the kind of sense – it’s called ‘Pit sense’ – where you get a sense of what the dangers of the underground are, and how you deal with them, how you cope with them, how you anticipate them. So, the idea of skill and a sense of the workplace, which is developed by workers themselves, is something that also interests and concerns historians of the working class these days.

Ethics of Work

One of the most insightful writers on some of these questions is the sociologist Richard Sennett. He was very influential in whatever I wrote, because he reflected on very slight kinds of changes. In a wonderful small book called The Corrosion of Character (1998), he discussed life histories of just six people in order to compare a commitment to work that existed in an earlier generation, compared to the commitment to work that exists in the generation that he was then surrounded by, and it’s a very interesting reflection. It gives us a sense of the ethics of working. It’s a completely different kind of realm of thinking about work: what is the ethics of work? What are the ways in which one thinks of what workers are guided by, apart from the rather dramatic strike actions, and so on. It’s called, as I said, interestingly enough, the ‘corrosion of character’. So, you can almost immediately understand that he’s talking about something that is lost in the new, especially, the gig economy – we will come to the gig economy.

From Large Scale Actions to the Everyday

In short, labour historians have moved away from large scale actions and protests to Alltagsgeschichte, the German term which refers to the history of everyday life: What does everyday life tell us about workers? It may not tell us or confirm our idea that they are heroic people – not necessarily. In fact, the person who coined this term, Alf Lüdtke (1943–2019), was trying to understand how it was that the German working class supported fascism. How were they complicit with the forces of fascism? They were doing those unheroic things. But in order to understand that, you have to study the everyday life of the workplace – workers in the workplace, and also outside. It was most valuable as a technique for understanding fascism, but also existing state socialism.

What is striking about our moment is self-exploitation. And this is completely true of the gig economy. Self-exploitation, into which gig workers have been pushed, throws us back to a certain kind of precarity that was true for the early stages of industrialization. We are talking about the 17th and 18th century!: the putting-out system in which workers had to work to the bone to keep their families together. How have we come here? We’ve travelled right across a phase where workers fought for their rights, limited working hours, better wages, better conditions of work, substantial kinds of welfare inputs, back to a situation where workers are literally thrown on their own resources, working themselves to the bone, in order to make ends meet. Any Uber or Ola driver you speak to will be able to testify to this statement that I’m making.

Feminist Interventions in Labour History

But there is another element or aspect of labour history that looks at the obverse of this phenomenon. And I’m referring here to the work of J. K. Gibson-Graham (Katherine Gibson and Julie Graham), two feminist geographer economists, who together investigated what happens to families when men are made to overexploit themselves. The people they were studying were doing not just two, but sometimes three shifts together. What happens then to family life? How were women coping with this extraordinary pressure of having absent breadwinners? What is the other side of the picture of self-exploitation? It’s a case study of mining in Australia. But this could be true for many other sections of the economy too.

The Role of the Outsider

I’m going to end this by talking about the outsider. An interesting and important thing for us to understand within labour history is that throughout the period of industrialization in India, and organised protest against unfair working conditions, Indian factory workers always relied on the outsider to represent their interests. In many cases, as you know, they were lawyers. Almost all representatives of labour were outsiders. By outsiders, I mean, that they were not necessarily workers representing themselves, but people who were speaking on behalf of labour.

Babu [Mathew] is a living example of this. When I was doing my labour history, I had done a long interview with Babu which I have the transcript of (I’ve been quite diligent in my understanding of Banglore labour history as well. Those of you who wish to can consult these papers). He’s a good example of this outsider leader. The necessity of the outsider leader was for reasons which I mentioned right at the beginning of this talk: the vast majority of Indian workers could not represent themselves, did not have an adequate understanding of the law, which became crucial in demanding the kinds of concessions that they needed.

I end on this note for a different reason: even the work of the historian is the work of an outsider. And I learned this to my utter dismay when I was making the film on the Kolar Gold Fields, and I realised that the workers were not that interested in their histories. I went to KGF at a time when the mines were closing; they were only interested in talking about the closure and negotiating a better severance package. They were not interested in their own histories. I was going there as a historian of KGF, and I knew the hundred-year history, the battle with caste and difficult conditions – the workers weren’t interested. It was a very interesting learning moment for me, because I realised how much of an outsider the historian also is. We have to deal with this.

Prof. Kamala Sankaran

I’ve worked on labour law and I’m going to use my personal research as an entry point to understand the material available for research. As somebody who has been teaching in universities for a long time, labour as a subject does not attract too many students. I began teaching over 30 years ago, it did not attract many students then, and I do not think it attracts many students now either. There are many reasons for this. But what is disturbing is that even amongst the government circles, the type of interest that labour attracted fifty years ago has diminished drastically. So, we see a gradual diminishing of interest in labour concerns.

Archives of Labour: Complaints to the International Labour Organization

What are the kinds of sources that you rely on while doing labour law research? My PhD research had looked at the complaints that went from India to the ILO, about freedom of association, and I tracked some 60 to 70 complaints at that time. I had to go back to parliamentary debates and legislation from 1919. The major sources were government reports, and you know, that the colonial government documented extensively.

As Janaki points out, while working class lives get lost, government policy is wonderfully captured in documents. As a researcher I spent long hours in the parliament library. When I was making these slides for today’s presentation, I realised that I could get a lot of material at the click of a button. There are also positives on documentation!

Parliamentary Records

At the parliament library, at that time, you had to take permission and could only go when Parliament was in recess. I was looking at the Legislative Assembly debates, for which one had to go to the Central Hall of Parliament, where the bulk of the older parliamentary records were located.

The Royal Commission Report (also known as the Whitely commission), the Factory Commission Reports, the Labour Investigation Committee Report (Rege Committee 1944-45) of the interwar period, and documents like the National Commission on Labour Report 1969 (the Justice Gajendragadkar Report) were complemented by the study groups of the National Commission on Labour which were prepared sector-wise and are a rich source of research material. The focus of the government reports shift gradually as you come to the mid-80s. Take for instance the Ela ben (Ela Bhat) Committee Report (Shramshakti – Report of the National Commission on Self Employed Women and Women in the Informal Sector), the National Commission on Rural Labour, and then the Second National Labour Commission on Labour (2002), and later the National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganised Sector (NCEUS) Reports. Since then, with regard to interest in labour matters, as you know, the fall is precipitous; there hasn’t been an Indian Labour Conference for just so many years. There are no agenda papers, nothing to rely on. The decline is devastating, there is barely any official reports/record keeping post-2007.

The Indian Council for Historical Research

The Indian Council for Historical Research brought out three-four volumes before that project was shelved. With that, a source of archiving labour documents also disappeared. So, for those of us coming to labour archives from a law perspective, there was limited official material other than court decisions. Some years ago, I was doing a study on collective bargaining agreements to see how women get represented. What you find is that there is no central repository of settlements entered into by trade unions and managements, whether in the public sector or in the private sector. I was looking particularly at coal mines, and at 2-3 public sector organisations, and at the tea industry. I was very interested in tea because of the wage question and the way in which wages were set, since a large part of it is set as piece-rate wages. It is very difficult to find data on wages settled through a process of collective bargaining in India.

Oral Histories

I highlight this book because I was one of the researchers for it. If you look at the labour history of India, on the labour movement and about different unions, you have, Sukomal Sen’s classic book for the history of trade unions, S.N. Dhyani’s works, KN Vaid’s books and the VVGNLI and AILH Archives of Indian Labour.

But on individual leaders, there’s not much. This book on Profiles of trade union leaders was published by the Maniben Kara Institute, a socialist trade union centre well known in Bombay. The book documents the lives of 101 trade unionists as a part of an oral history project. I recorded some of the interviews which the Maniben Kara Institute transcribed and edited. I had just completed my LLM, when I took up the project. I had been contacted by Sarath Davala who was then in the FES. The raw tapes may also be available. When I look back, I was not trained to do labour history. I was given this tape recorder – a Walkman with some facility for recording and I went and I did some of the interviews.

I want to talk about individual leaders because the sacrifices and the work that a trade union leader undertakes in his or her lifetime is incredible; you need to see the work that they do.

B.D. Joshi (All India Trade Union Congress)

I’ll begin with B.D. Joshi (AITUC) – perhaps you knew him, Babu. At that time, he was living in Delhi. I visited him and his family two – three times. He was already quite old. He would make me sit around his dining table and have several cups of tea while he talked. He was well-educated and joined the Shimla Himachal Pradesh government as an employee, and he said something like, “I was very happy I got employed in the dispatch section, because I send out trade union literature to various people”. He said it was a very risky job and he eventually lost his job. He went on to become the leader at Delhi Cloth Mills. If you’ve been to DCM, the Filmistan bus stop in Karolbagh, you’d know that the workers’ quarters were there. And that’s where he worked. When the DCM closed down, he went on to do other things.

RK Bhakt (Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh)

I’ve chosen to talk of one leader from each political affiliation. RK Bhakt was from the BMS. It was the first time I went to the RSS headquarters in Jhandewalan in Delhi. I went there a couple of times because he was an RSS activist and he stayed there – an austere person, very serious and committed, and one of the trade union leaders who was himself a worker. He was a municipal worker, who led the great struggles in Amritsar of sanitation workers and was a cadre of the RSS and rose to become a higher level organiser in the BMS.

Dr. MK Pande (Centre of Indian Trade Unions)

I met Dr. MK Pande who was President of the CITU for long years many times for my own doctoral work which looked at complaints of trade unions to the ILO. The greatest complaints were filed by either HMS, or by CITU. He was an academically-minded trade unionist; he went to the Gokhale Institute in Pune where he did his PhD. He was deeply interested in academic work. So, he was very interested in my PhD, my research questions, my methodology, the oral history project – the kinds of questions that I didn’t get from other people I interviewed.

Kanti Mehta (Indian National Trade Union Congress)

He was a Gandhian in the Congress. He was a great leader of mine workers. He was in the governing body of the ILO. He set up a centre for mining workers. I met him both in Delhi and in Puri. He and his wife had worked during the Bengal Famine. He had worked in the mines, and I gained a lot of understanding about different types of mines and conditions of workers in opencast mines, deep mines, people working on the rock face and with the trolleys.

We also talked of the Chasnala mining tragedy, one of the worst mine disasters in India. Today people speak about Chile and mine disaster there, or they may know about rat-hole coal mining in Meghalaya, but not enough about the Chasnala mine tragedy. There’s very little documentation. This book has an edited version of the longer interviews, done with FES funding.

There is a great need to capture the oral histories of people who work at different levels in the labour movement before it is lost.

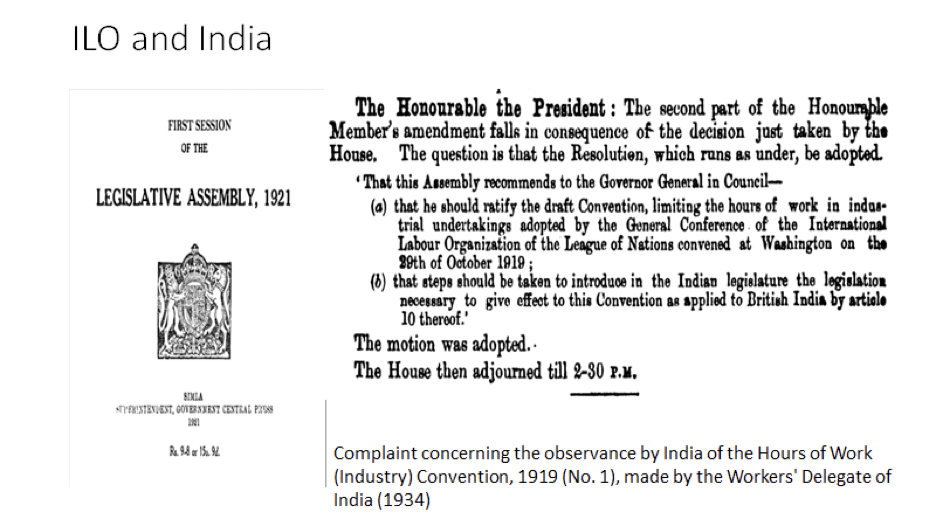

Parliament Debates about Hours of Work

Yesterday was May Day, and about the demand for an 8-hour work day: One convention at the ILO – the Washington conference – was on fixing the hours of work. The hours of work were fixed at eight hours for the Global North. But in India, it was extended.

There’s a history to this, particularly when you look at the loco-running staff. If you look at the loco- running staff, the people who run the engines always came from Bombay. Peter Alvarez, who was the great iconic leader of the All India Railwaymen’s Federation AIRF, was from Bombay (The engine drivers were largely Anglo Indian – an unanswered research question). I had interviewed another AIRF leader JP Chowbey in the AIRF office.

I want to share with you a glimpse of the debates in the Legislative Assembly at that time.

This is from 19th of February 1921. The ILO adopted Convention No. 1, which is the draft convention on limiting the hours of work. This was the final resolution that was adopted, that India and the Indian legislature would give effect to this Convention. A complaint was filed in 1934, against the observance of the hours of work. And again, it came from the railway loco-running staff who used to work for 11 hours, and an engine driver could not go off duty till a replacement came. If a replacement didn’t come for one shift, they just drove the trains for 24 hours.

I say this because, during COVID, remember, and last week, Tamil Nadu increased the working hours to 12. Yes, it was withdrawn yesterday. The point is that if you were to look at the proceedings in Parliament, this resolution [points to archival record] about whether we should rectify the problem comes at the end of about 40 pages of discussion. You will be hard pressed to find a debate of such a meaningful sort on changing the hours nowadays. So, these are archives which also show you how standards of governance have changed.

Informal Work

Let me move to the last two things that I want to say. Informal work is very poorly documented. It’s not documented even in government data. On the question of wages, because Janaki raised it: There is self-exploitation because they are paid by piece-rate. And if you don’t work longer hours, if you don’t induct your entire family into beedi rolling for example, you won’t even make the equivalent of a daily wage.

Rajnarayan Chandavarkar who worked extensively on Bombay, also tracked whether there was a longitudinal shift, from time- rate wages to piece-rate wages. This is one of a few studies looking at shifts in wage fixation. The other one is by Sharit Bhowmick who looked at the same thing, not in textile mills but in the tea estates. And you can see a longitudinal shift from time rate to piece rate work, but history has come full circle, and you will see a resurgence in piece-rate wages in platform work.

Changing Types of Archival Records

On the WIEGO Law and Informality project, I worked with Roopa Madhav where we studied informal employment in India and three other countries covering domestic workers, waste pickers, street vendors, forest and fish workers. We worked on this project this ten years ago, and other people are working now on this now. The types of materials the project collected were interesting: advocacy materials, drafts of various bills/legislation, fact sheets, presentations, reports, research, case studies. So, the nature of the material that’s getting generated now is different from the way in which labour archives were imagined in the past. We need to look at that shift.

Private Members’ Bills as Government Interventions

I’m going to conclude with a set of materials about domestic workers – Geeta [Menon] knows because I interacted with her as part of that project work. We also did studies with fish workers about whom there is less material and research conducted, compared to street vending and domestic workers. We tried to collect a whole lot of bills, and many private members’ bills. I’m taking up a private member’s bill, by Dasari Narayan Rao. Collecting government interventions, apart from the debates, is also useful.

Moving Forward: Archiving Online Material, Oral Histories, Court Cases

To make a few final points,

One, to interest a new set of students in the universities who are looking not just at dry government material. And to interest them, we need to understand how we should archive material that is on the internet, material that people prepare in scattered ways, and try and see whether young people would be interested.

The other is about the lives of people who organise. It is very inspirational, because you’re archiving oral history. I’m sure there are better ways to document than the way I did as a young researcher, which was asking questions, and using my political antenna to get stories out of them. I think that that’s an important task.

And the third is to use cases that come up in court: the challenges to collective labour cases are few and far between. They are usually individual disputes, which are taken up in court, but the big disputes say, like, wage settlement – the wage boards have disappeared. Industry-wise settlements have diminished. Increasingly labour disputes in court are individual based, and that is eating away at the organisational reach of trade unions. Since we are at NLS, we might think about how we use court cases to mine something out of them.

Prof. Babu Mathew

Dear friends, this is the first opportunity of its kind at the National Law School for me since the time it began. I’m so happy that I could speak last, after listening to two scholars on the subject, and my presentation will be of a different type. I wish to share a few highlights from my own trade union experience, largely in the city of Bangalore. And yes, I remember Janaki as a journalist from the Indian Express. She was one of those whom we could trust, because the interviews that she would have with us during the course of many a strike, was very well covered in the newspaper. And that was a great help to the trade union movement. I think, at that time, we had at least three or four journalists with the same approach to trade union struggles. I doubt whether we can find them anymore. And so that was indeed a good experience.

Unionisation in Public Sector Factories in Bangalore

Listening to Janaki, I put down some thoughts and those thoughts fall broadly into two categories. One is my experience with public sector factories in Bangalore. You may know that there is no other city in India, in which five major public sector undertakings were situated. That’s the uniqueness of Bangalore. It consisted of Hindustan Aeronautics, Bharat Electronics, Hindustan Machine Tools, Bharat Earthmovers, and Bharati Heavy Electricals. And, mind you, all of them were unionised by the time I got into the trade union movement; my predecessors had already carried out extraordinary struggles to set up trade unions in those public sector undertakings. HAL, I think, had a history even before independence, and a lot of versatility.

I also remember a trade union leader of great importance in Karnataka with whom I worked – his name is M.S. Krishnan. Janaki will surely remember that name. He was given very high recognition in the Hindustan Machine Tools factory at a time when Nehru went to inaugurate the factory. So that’s also a kind of a reflection on what kind of an approach Nehru had. I am now convinced after many years of reflecting on it that, for him, industrial policy, industrial policy resolution, as well as the Industrial Development and Regulation Act of 1951 – in other words, the industrial policy – had to have a corresponding labour policy. And so there was coherence in his approach to these questions. And that clearly manifested. It does not mean that there were no problems in these factories and in these unions.

When the Green Flag met the Red Flag

But the most outstanding memory in my mind is an occasion when in northern Karnataka, in two places called Nalgund and Navalgund, peasants were shot dead. And in protest, peasants carried a flame and walked all the way, about 700 kilometres, to reach the city of Bangalore. And I have extraordinary memories of how the peasant jata, the green flag, was received in one industrial city after another with the red flag. By the time they came to the Tumkur Road area, which is where I was working – we had a concentration of Trade Unions of like-minded nature – we had organised food for the peasants. We asked workers to make chapatis and bring it to share. And I remember the room in which the chapatis were stored – Chapatis had reached the ceiling! And that’s the kind of solidarity that was expressed on that occasion. In my mind, it was like a festival. I say festival because I’d never seen a reception for a peasant movement in the city of Bangalore of that nature.

And you know what policemen do whenever there is a procession. They come and harass you, “Are you following the right route? Which part of the road are you occupying?” But when this Jata came, all the senior police officers, including the commissioner, were behind the procession. That was the kind of momentum that the procession generated. Of course, it was peaceful, and all along it was welcomed by people in the city of Bangalore. I remember passing through the neighbourhood of a school, the children had climbed the top of the wall, and they were waving out to peasants whom they had never seen before. So, there was something in the air, which accelerated the whole process. And it was brilliant that the green flags and the red flags met each other.

There was an extraordinary public meeting and that mobilisation coincided with the strike of the public sector workers. Public sector workers were on strike for over 70 days. That’s another fantastic memory. That was a peaceful struggle throughout, and those who came from different parts of India, and different parts of the world, to see how the public sector strike was going on, they all pointed out that this was extraordinary: there was no picket line, and yet the picket line was observed, meaning nobody broke the strike. There was a100% observance of the strike.

But we had a very clever police commissioner at that time, and he played havoc by making sure that the mobilisation of the workers did not go beyond the control of the law-and-order machinery. I recollect the kinds of negotiations he held. This is just to tell you how clever they are. And they could take pretty senior trade union leaders, in my opinion, for a ride.

The best part of that public sector strike was that the workers of the public sector in Bangalore were spread out into every corner of the city of Bangalore. They all formed, in response to the oppression, Mohalla committees. You can imagine that that was a very powerful democratic process – far more important than the 74th amendment. It was not just the municipal council – you can compare it to the booth committee. Yet, it’s sad when we reflect on it, that that legacy and that opportunity were not taken forward.

The best thing about all the public sector undertakings, was that we had workers from all over India: all language groups were present. And never have I seen friction between language groups or caste groups or religion. Workers were united in the public sector. And of course, there was trade union rivalry, especially in those factories in which all the trade unions were present. There were a few like Hindustan Aeronautics and Indian Telephone Industries, where they had an independent trade union, but all the other trade unions had trade union rivalry. I was also a part of one such trade union.

Look at the new Industrial Relations Code – the process of legislation is complete, but not yet brought into force. This new Code has a very interesting provision in it. For the first time, at a national level, if this Code comes into force, we are going to have recognition of trade unions on a compulsory basis.

Collective Bargaining

I remember Reena [Fernandes], who is sitting here, was the one who led the hospital workers movement in Bangalore, along with another colleague. And in the early days, we had to fight for recognition. Private managements never recognize unions easily, but we followed some processes and the conditions were favourable. If they were to form a trade union in an establishment, a factory or a hospital or a school, or a hotel, our precondition to the workers was, everybody who works in that establishment must join, “If you are not yet ready, if you are not going to give us 100% membership, don’t worry, please go and tell the workers that this trade union will come only when everybody gives their membership.” We had that great advantage, and that gave us a tremendous amount of strength in the negotiating process.

So, I must say that, even though there was no law relating to recognition in the public sector, we broke grounds, that is, all the trade unions would come to an understanding among ourselves, and then go to the management, negotiate with them, and enter into what is called as a 12(3) settlement, where the management agreed with the trade unions to carry out a secret ballot. A secret ballot, mind you, which the new laws are hesitant about. And on that basis, they recognised trade unions. Sometimes, if no union got 51% of the votes, then all the unions formed themselves into a bargaining council. Those of you who are familiar with Labour Law will notice that this is a tremendous advantage. And a leap so far as collective bargaining is concerned.

Strangely, the new law allows that, but of course, it doesn’t allow collective bargaining in clear language. It appears that it could be left to the state government, through delegated legislation, to tackle that part of it. Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Chhattisgarh had invited us to help with a rulemaking. We’ve been able to introduce secret ballot through rulemaking. The reality in India is that central trade unions have rejected the four important labour codes. I think the predecessor to that is the public sectors of Bangalore where the central trade unions were active.

And just as it was pointed out, we had CITU leaders, BMS leaders. The BMS trade union leaders with whom I worked in the city of Bangalore, were clean people. They led an austere life. Those of you from Bangalore may remember the name of Alampalli Venkataram. He lived in a small room in the heart of Bangalore. I’ve been to his room, with a kitchen and a dining area, and a sofa library. And above all, he had paper cuttings, which would reach the ceiling. And he would always come to a labour meeting with relevant paper cuttings and read them out one after another. He was a very devout trade union leader. And despite him knowing that I was a Christian, he did not have any problem with me. We had very good relations, right through. So that’s another experience.

In the public sector undertakings, there was one so-called ideological problem, primarily, within the left framework. I was in favour of productivity-linked wage settlement in the public sector, despite opposition from other central trade unions. There was a double standard, where with the private sector, a productivity linked settlement was alright, but despite that, ideologically, you would not like productivity-linked settlement with a public sector undertaking.

Unionisation in the Private Sector

Let me mention a few experiences in the private sector in Bangalore. There were several hundreds of small-scale industry, medium industry and large industry. I think the most outstanding feature is the fact that we had collective bargaining settlements in almost all of them. I’m aware of more than 100 good collective bargaining settlements, signed one after another, in small scale industry, medium industry and in large industry. Meaning, managements also felt that if they want productivity and quality, it is good to have a trade union which is reliable. And in that process, there were many collectives- not as if it was easy, there were always strikes. And I was fortunate to associate with a number of strikes, and I must say, more than 90% of the strikes were successful strikes.

Of course, more important than a strike was the strike notice. A strike notice is even more powerful than a strike. Through those strike notices, we were also able to reach very good settlements. I remember one particular factory. The Chairman and Managing Director had an engineering background. His approach was very different from somebody who was from, let’s say, a moneylender background. There are industrialists who come from that background also, and the attitude will be quite different. The one I’m thinking of is Widia India, a very big engineering factory on Tumkur Road. He made sure that there was timely diversification. And therefore, there was never a question of excess labour. The labour force at that time – it was about 1200 – was never reduced. It was shifted to engage in another product in the same factory. So that is, I would say, a brilliant method of management and industrial relations. That way, we came across many committed people.

The Picket Line

About our struggles, I want to recount one particular episode, and that is about the picket line. The police decided to support breaking off the picket line, which is illegal in terms of the law.

The Industrial Disputes Act recognizes that breaking a legal strike by recruiting new workmen is an unfair legal practice. However, that is what happened. That was a very cruel management, and a management which could afford to bribe the police. So, they broke the picket line. There was police lathi charge. And in this particular lathi charge, the police van was used to ram against the gate because workers had jumped into the factory. They rammed against the gate three or four times till they bust it open, and a policeman was chasing the workers. The workers knew their factory, but this policeman didn’t know the factory, and he ran into a space covered by glass. So, he got a gashing wound, and started bleeding. It was clear that he would die if he was left unattended.

The police officers said they had no way to rescue him, because, by then, the rasta roko was on and nobody could enter in a radius of about 10 kilometres around that factory. So, the policeman appealed to us, ‘You’re the only people who can save him’. We thought about it; we took this policeman, put him on top of our jeep, carried him through and handed him over to the police department. I want you to know that even in the middle of a struggle, that kind of logic was always present, though it is the same policemen who were resorting to lathi charge. There are interesting stories of this kind.

One mistake we made that I remember was during a procession. I was at the head of the procession. We were about to face lathi charge, we knew it was coming. And so, somebody advised, “Put the women in front of the procession, then the police will not attack.” Foolishly, we agreed. Women workers were brought to the head of the procession. And poor women, they got bashed up, including with tear gas on their body and their chests. And I remember one woman took a long time to recover. So, some of these notions about how a policeman may behave, is crude imagination from our side.

While talking about private sector strikes, I particularly remember Stumpp Schuele Somappa. It is also a factory on the outskirts of Bangalore. That factory decided to violate Chapter 5-B of the Industrial Disputes Act, that is, you can’t lay off [workers], you can’t retrench, you can’t close without government permission. And so, the matter went up to the High Court. In the High Court, and I’m taking the liberty of mentioning the name of the judge, Justice Rama Jois. He stood in favour of the management. But his judgement was brilliant. As a result, it was very difficult to handle that particular judgement of the High Court. Of course, we had to bring lawyers from Delhi, RK Garg came. We argued, and in the division bench we got relief. But I’m pointing this out to you: When you have a right-wing judge who’s very intelligent, then these judgments are far more difficult to overcome than the ordinary judge. And this particular judge who I’m speaking about, some of you know him, had that particular quality, which only added to the difficulties that we faced.

I must then jump to a recent experience: We collected and are yet to analyse 14 wage settlements during this period of bad labour law. All those 14 wage settlements indicate very attractive wage increases, and very few contract labour in those factories. Why do you think that has happened? That is because they are all pharmaceutical industries, and they want productivity in order to meet the market requirements. It is worthwhile to look at collective bargaining agreements even now, in order to check whether it’s a factory that’s interested in quality and productivity, in which case they themselves will look forward to stable trade unions.

I think I will end there. I only want to mention in passing that, you know, wherever we have encouraged internal leaders to take over the leadership of the trade union, it requires quite a bit of training. One such factory in Hosur (in Bangalore) of General Electric went on a strike. The internal leaders handled everything. There, militancy was far higher than what it would have been, had there been an external trade union leader. As a result, there was a prolonged strike with no settlement. Finally, the factory closed and moved away. So, that is also an interesting dimension. When you empower an internal leader who knows how to negotiate, they have the ability to muster support in a manner in which the strike can carry on indefinitely.

I found that on Tumkur Road, the best part of our strikes were an alliance with the local villagers. And so, it was easy to carry out the struggle of 100 days, because there was food provided from the villagers. That would be used in our strike tent. We got a reputation that if these guys don’t go on strike, it’s not easy to defeat them. That helped us to get into negotiations.

The last thing I want to mention is recent experiences with garment workers in Jordan, at the request of the ILO. And what we found in our report is, wherever we had sharp references relying on ILO documentation, ILO standard simulation to recognition of trade union and collective bargaining, the ILO itself doesn’t believe in it anymore. I think the time has come to take the ILO to task saying they have shifted after neoliberalism. They’re no longer taking care of the standards required to protect workers.

Thank you.

Discussion

Questions

Geeta Menon, Domestic Workers’ Rights Union

I have not so much a question to the veterans, as much as an observation. Oral histories and the history that we read, or we gather from, should also give us some answers for the present. Whatever the trade unions and political movements fought for in the past is being reversed today. The present becomes history tomorrow. What is fascinating today with the market changing is the matter of identities. Identities of workers have to be seen more as social identities – not just as workers anymore, because there is no working class. I’m talking about the large informal economy that does not have one kind of working class. The IT sector has thrown up another class of workers. Definitions of who is a worker and employee have changed.

While workers at the factory lift the red flag, their social identities take on a different colour as soon as they return to their residence. With increasing marginalization and invisibility, what are the elements of history to be gathered, developed and taken forward?

We work with domestic workers. The domestic workers rights union is based in Bangalore, Mangalore and Belgaum. Domestic workers are last in the hierarchy of work, and a majority are women. We work with full-time, part time, and migrant women workers. There the issue of trafficking comes in, in the idea of unsafe labour. Hence, mobilizing takes on a different character from regular trade unions.

Question

Thank you so much for a very inspirational as well as informative talk. As a much younger scholar working in the field of labour, it was rewarding for me to listen to your different perspectives. I have two questions and a comment. One relates to the documentation that we are not seeing – such as after the second national commission of labour, it’s almost as if government official reporting on labour has collapsed. Even the changes happening right now are not on the basis of an official study or rigorous documentation. From that angle, as an archivist, what should the role of academics and researchers or more importantly labour activists be, in trying to create records for the future?

The second was to take off from Prof. Babu Mathew. There are many unions today which find space from industry because it is recognized that labour rights are not antithetical to efficient operation. In their own self-interest, there is a case for more protective labour conditions in those establishments. But if that’s not the case, in most industries – thinking of domestic workers unionization or that unions of gig economy mobilize differently from the way it was done public sector enterprises – what lessons can we draw on and replicate in some of the new forms of industries? And what are the specific challenges that we must address for which we can’t replicate the same methods that were used in the past?

The third is more of a comment. Being obsessed with railway timetables and a few other things, it was the policy of the colonial regime to not hire anyone but Anglo-Indians as engine drivers in the early years of expansion. North Indian railway stations even now seem like forts as a supposed refuge if there were a repetition of 1857, and as a policy it continued into the 1950s and 60s.

Question

On the putting-out system, could you link it with the gig economy and how the worker is recognised as a worker? That’s something that the Labour Commission has been trying to pull out.

Question

Is there any longer a field like labour history which is separate from other histories?

Responses

Janaki Nair

Let me start with the last question, about the blurring of the boundaries between labour history and other kinds of history. It seems like that partly because the object of inquiry has shifted away from only work to, as I mentioned, neighbourhoods, questions of leisure, religiosity etc. There I would disagree with what the Babu said. From the 1950s onwards, questions of language and so on, began to affect public sector units in a way that led to the establishment of Kannada Sangha and so on, which were quite strong. In fact, Kannada Shakti Kendra ruled in HAL.

But anyway, all I’m saying is that, labour historians recognized that the picture of the history of labour cannot be confined to the workplace. Each time I taught the labour history course, I found that students were interested in knowing about non-workplace histories, more than they were interested in workplace histories. Having said that, what we’re faced with is a radical transformation in the very nature of work. The repertoire of actions such as organised strikes, and so on is appropriate to the 19th century factory form.

Here, I would like to be corrected by somebody like Babu who is an activist, but we do not yet have a repertoire of actions that are appropriate to the new workplace. And the new workplace, as you know, is a diffuse workplace. For example, there are care workers who are going to individual homes, not necessarily going to any central location, not massed in numbers like factories had mass workers. So, our tactics have to change according to the nature of work itself. And I think Geeta is doing a marvellous job in terms of aggregating domestic workers who are by far the most dispersed, in terms of getting them to think of themselves as members of collectivity. How do you convince people who are disaggregated, individuated, to think about themselves, as part of a collectivity? It is a very hard job. But I think it is happening, and it’s happening across many sectors. And it’s happening, interestingly enough, from within. It’s not necessarily outsiders who are bringing this knowledge of the importance of collective activity to workers. For instance, the kind of actions undertaken by gig workers in America in the automobile sector, of switching off the apps for a certain period. That is, responding in terms of tactics that are appropriate, the nature of the work, the location, and the ways in which they will actually disrupt the service being provided enough for people will take note.

Kamala Sankaran

I will begin with the last point too, that there is a dispersal of the workplace. But I would like to flag that informality was always a part of the Indian scene. What does it say about the domination of Eurocentric thought on Indian intellectuals, including trade union leaders, that failed to recognise it for the longest time? The domination of the global north in terms of classification of workers, the way production is carried out, the near invisibilization of the fact that informality was the norm here and not the other way around. I think it speaks a great deal to the intellectual burden that we carry. If we don’t address that, we will always be latecomers to theorization.

Second, contractualization of the public sector enterprises began around the 1980s. For a long time, trade unions did not organise the contractual workers for various reasons. That is a matter for reflection. Contractualization and casualization has gone on a great deal. The atomization of newer forms of work, where you are at home or you are bidding for work, and you’re left defenceless, in the face of the fact that even though these platforms do not make money, the financialization of the world has happened to such an extent that the venture capitalist is beginning to bankroll a platform that doesn’t make profits for 10 to 20 years. The financialization of the world economy is something that one needs to address. The dissipation of the workplace means that you need to look at newer forms of organising. People need to prepare to even protect their existing conditions.

Regarding the post- 2000 collapse of the government-as source-of-documentation: After the Arjun Sengupta Reports of 2006 and 2007, which continue to be the benchmark for a lot of informal work, there’s hardly anything. So, who steps up in that case? Private researchers do some research based on funding. Where is that going to lead our research is a very troubling question. Because for the longest time, many government reports were doing the documentation. Can there be forms of documenting from secondary sources? I was just suggesting legislation and court cases.

About Anglo-Indian recruitment, I’m not sure that I could make a sweeping statement. People have been writing about the peculiarity and ethnic profile of the loco-running staff. We know the railways always served a double purpose. They were crucial lines to be protected. Whether the railways saw the kind of recruitment that we see in the Indian army which was more explicitly recruiting on grounds of community etc, I’m not sure that one could see such a pattern. Generally speaking, in the railways, there has not been that kind of distinct recruitment that one has historically seen in the military.

Regarding the newer forms of informalized work in the formal sector and in the public sector, note the precipitous drop in trade union densities, being one of the lowest anywhere, even in terms of the numbers of collective bargaining agreements. Instead, you have other forms of negotiations that take place. Will the forums of representative democracy be the appropriate forum for people to put forward their concerns? A lot of out of the box thinking has to happen. And it’s certainly a broader issue than just a labour matter.

If I can make just one last point, regarding the use of criminal law to settle labour law matters: we’ve seen world over, a trend towards civil remedies being used for labour factors. But India has always used civil and criminal methods. It isn’t likely to change.

Babu Mathew

I must begin by mentioning that even in small scale industry, because of tremendous fragmentation in an industrial area, you will have engineering, automobiles, pharmaceuticals – a whole range of industries. And therefore, given that structure, thinking in terms of industrial unions was very difficult. Therefore, there was a long history of fragmentation. Almost every single case where the union is formed for the first time, there would be repression, and an attempt to victimise the office bearers. It’s only as a result of unionisation that that could be prevented, meaning, almost invariably, there would be a confrontation, largely for the sake of at least de facto recognition of unions.

Unionisation has never been an easy job, except in, you know, the public sector where there’s a long history, and unionisation became the norm. In the private sector, it was always a difficult task. And I say this in order to emphasise that there’s no shortcut to it, whatever the situation. Of course, we may have to adopt new methods of unionisation. For example, such as Shankar Niyogi would do: unionisation was in the place of residence of the workers, not at the workplace. Through that kind of experimentation, some new kinds of units are picked up.

If you look at what Geeta has been experiencing and achieving among the domestic workers, and many colleagues like Geeta in different parts of India, I noticed that probably the maximum amount of energy from below comes from domestic workers. They are struggling, and there is a tremendous desire to unionise or to fight for labour demands.

The past ambience has changed. The Labour department is no longer sympathetic to labour at all. They have become management departments. You can’t expect any support, unlike what it used to be in the past.

I agree with Janaki that there cannot be the same old type of forms of struggle as was possible when everybody was under a common roof. It’s not a continuous strike for so many days that’s going to matter. It will have to be mobilisation as it would happen on a Mayday. Even now there is a tradition that workers from different organisations come together. And in that sense, the time is right for the informal sector to get unionised.

I would sadly say that central trade unions are now almost an obstacle to the unionisation of informal workers. This is because they have developed the habit of rivalry. So, informal workers always require a platform in which many independent unions will come together, and we’ll be able to act together. But if they want to act together, the obstacle is central trade unions.

And so that’s a factor, though it can’t be denied that central trade unions also helped in the struggle. But creating platforms, with independent unions spread in different places – that process is happening. There is a national platform of domestic workers. There is a platform of gig and platform workers.

We have been working with gig workers’ issues, and we are addressing the question of ‘Are you a worker or not a worker’. There are two approaches to it: One is, local jurisprudence is shifting marginally now in our favour. Workers are being called workers in many jurisdictions. The typology available in labour law in India – there are laws which are crafted on the basis of not becoming a victim of a definition clause. You don’t necessarily have to be called a worker. We are trying to say, any person who works in this or this place, whose occupations are listed in the schedule, will be covered by this legislation. And that legislation may address all the different types of rights of workers including unionisation and wages and social security and hours of work. So, the Indian legal regime facilitates very creative law making, which means there has to be continuous interaction between those who know labour law and the activists.

I think there is a lot of scope for that. And it must grow beyond a city level. I think it must go into the state and national level. And that potential certainly exists. So, my last word on that is, I don’t think there’s a shortcut to unionisation, it will have to be done in the new circumstances. And after all, we still have freedom of association. And I’m one of those who welcomes the new provisions in the industrial relations code, so far as unionisation and, above all, recognition is concerned. We must invoke those provisions and push ahead.