QAMRA | 15th June 2023

Following three months of conversations and planning, the QAMRA Archival Project, NLSIU and the Lesbian Herstory Archives, NYC met online on 4 March 2023 in an exciting inter-generational conversation, where LHA archivettes Saskia Scheffer and Olivia Newsome took viewers through an online tour of their building and collections – watch the tour below!

Our tryst began in December 2022, when QAMRA’s advisor, Siddharth Narrain, put us in touch with Joan Nestle, co-founder of the LHA (since 1974), and Karen Engle, Founder and Co-director of the Bernard and Audre Rapoport Center for Human Rights and Justice, UT-Austin. Subsequently, publisher Sinister Wisdom sent us a copy of Joan’s selected writings, A Sturdy Yes of a People (2022). The book is divided into five sections: Liberation, History, Sex, Education and Archives.

In her essay, The Will to Remember: My Journey with the Lesbian Herstory Archives, Joan begins with a memory,

“The most searing reminder of our colonized world was the bathroom line. Now I know it stands for all the pain and glory of my time, and I carry that line and the women who endured it deep within me. Because we were labelled deviants, our bathroom habits had to be watched. Only one woman at a time was allowed into the toilet because we could not be trusted. Thus, the toilet line was born, a twisting horizon of lesbian women waiting for permission to urinate, to shit.”

In the inaugural essay of the book, My Mother Liked to Fuck, Joan writes with a daughter’s wisdom about her working-class mother,

“Respectable ladies did not speak to my mother for most of her widowed life. She picked up men at the racetrack and at OTB offices, slept with them, had affairs with her bosses, and generally lived a sexualized life. Several times she was beaten by the men she brought home. In her fifties, she was beaten unconscious by a merchant seaman when she refused to hand over her paycheck. My mother, in short, was both a sexual victim and a sexual adventurer; her courage grew as voices of condemnation and threats of violence increased against her. I watched it all, and her belief in a woman’s undeniable right to enjoy sex, to actively seek it, became a part of me. But I chose women. I wanted to kill the men who beat her, who took her week’s pay. I wanted her not to need them and to come into my world of lesbian friendship and passion, but she chose not to. We faced each other as two women for whom sex is important, and after initial skirmishes, she accepted my world of adventure as I did hers.”

Moved and desiring to hear more from Joan, we recorded an hour-long conversation in January 2023, an excerpt of which we played at our event in March.

Speaking of the McCarthy era of the 1950s, and having attended the hearings of the House of American Activities Committee at 17 years, Joan learnt, “If you are going to be different, you are going to understand what dehumanization means.” In that time of anti-internationalism, she told us, “Being a communist was like being a queer.”

In the 1960s, in the midst of many radical civil liberation movements, Joan joined the SEEK program (Search for Enlightened and Educated Knowledge) founded by Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman to be elected to the US Congress and also to run for US President, “It was meant for the Black, Hispanic students and later all the migrants who didn’t get a decent education in high school… To prepare to teach, I read Albert Memmi’s The Colonizer and the Colonized… And it prepared my soul for my future work with the archives. The colonized was never given an opportunity of their own history. At best they are allowed a few names. The colonized are always condemned to lose their memory.”

The Lesbian Herstory Archives began in Joan’s apartment, in a milk-crate, and from the sound of it, there were few walls between the women, the movements and the archives. On the role of memory, she said,

“My body was learning on the streets of my city how to take a position – with others, always with others, comrades always – of defiance. And then, the Archives is a site where memory takes a position of defiance.”

Online Tour of the Lesbian Herstory Archives

Saskia Scheffer (wearing a t-shirt that said Every Dyke is a Hero) and Olivia Newsome took viewers through a wondrous tour of the LHA collections.

Among the highlights were the Subject Files, where many researchers begin, and as Saskia riffed through some of the ‘I’ folders we saw, Illness: cancer, chronic fatigue, Images, Immigration: homosexual ban, Incest, International lesbian movement.

We saw a few images from the Tee Corinne collection, an artist famous for the Cunt Coloring Book. Saskia was quick to reiterate, “You do not need to be famous to be represented in the archive!” We saw artist Anna Campbell’s marvelous tribute to the LHA: bronze fingers cast from archivettes’ fingers that are used as hooks to secure the library ladder. While there is little to explain about the symbolism of fingers to lesbians, the hooks are a testimony to the safety and protection of lesbian herstories by the archivettes.

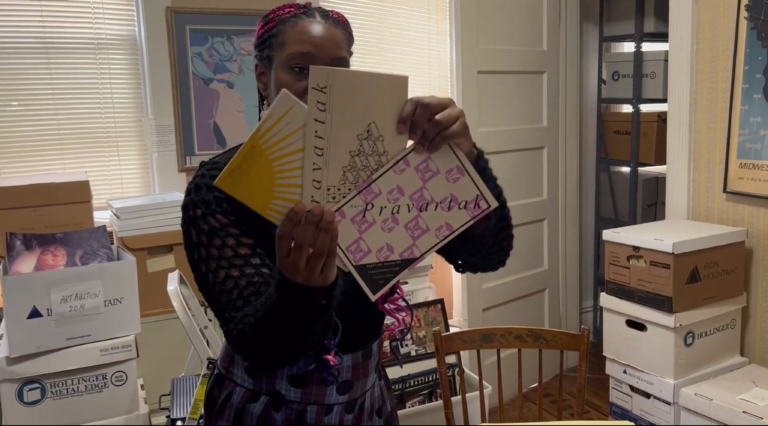

Olivia pulled out many South Asia specific magazines, including publications by CALERI and to our surprise, several copies of Naya Pravartak, special because Pawan Dhall who helped publish them was in the audience.

Responses

In her response, Jaya Sharma, a feminist, kinky queer writer and activist who lives between Delhi and Goa, and whose voice resides at QAMRA, drew on Joan’s thoughts on race to speak of memory in the context of Islamophobia. She called our attention to the need of queer archives to “be the memory of complicity, to map the shifting battle lines, to map the messiness between us and them [because] the ‘them’ is not very clear these days.” Jaya’s thoughts sparked off a wonderful discussion among the group and widened the ambit of what queer archives may house. Speaking of the prevailing climate of fear, she said, “The feeling that I get from archives is the feeling of being held, and I think there is a sense of continuity – not just of being connected with older generations but a kind of continuity of collectively witnessing what is happening, of witnessing the ruptures in a way that makes the horror-show less horrific because safety is one of the things that we heard being talked about… In this moment, what we need are voices – queer voices – from outside the country about what is happening in India and there is not much of that. And I hope that queer archiving records silences, and records shifts in silences. Because that silence will hopefully break.”

In the ensuing public discussion, Ponni, Poorva, Sristhi, Louisa, Joan and the Bombay People pitched in to deliberate on the dilemmas of archiving queer histories, of archives as safe spaces to have difficult conversations, to ask whether queer archives must house fear when State archives do a good job of it anyway, as well as the joy of finding connection and oneself in the queer archives.

Archivette Amy Beth spoke of collections affectionately called ‘Enemy Literature’ at the LHA, “There are points of difficulty – there are visitors to the archive who say, ‘Why is this in here? This taints and destroys my otherwise necessary experience of all the rest that you have collected.’ And for us to say: There will be room here because it still depicts the experience of lesbians. Women who got taken to court and lost custody of their children because they left their husbands to be with another woman, for example. In having to contend that both will be together in this space in this spirit. There is a continuum of experience in our lives.”

Concluding Thoughts

Flavia Rando, a long time archivette, returned to the question of inclusion and exclusion to say, “We had people who didn’t know where they were going to sleep that night and slept in our meeting rooms. I think it is this very factor – the liberation of all people very explicitly, that was so dangerous. In many stories of the queer movement, we have been written out. I think that it is still dangerous. Dangerous is good.”

Amy Beth framed her thoughts in terms of self-description: that to be Jewish is to live with an obligation to memory. Speaking of collections, she emphasized the importance of not turning down any format, “Ask the donor to sit down and write a few sentences about how that pamphlet managed to get printed – who passed it to whom, where in the night, or time of day, who couldn’t put their name to that pamphlet but they brought the ink. It is the fully comprehensive narrative where we don’t become a people who are subjectively described – it is about us, by us. Take the time – 60/40 cotton poly is not as interesting as asking where did you find the person who did the graphic, to ask how old are they, what did they do other than design t-shirts or if they don’t design t-shirts.” Speaking of her time at the National Archives of India, she said that a history of the nation could be written through one fibre – cotton – and that is the kind of attention that could be brought to queer archiving, “Tell me about your life using t-shirts.”

Paula Grant, who has been associated with the LHA since late 1979, spoke of the importance of reaching out to community, “I had the good fortune to go out to wherever people would have us – church libraries, basements, and say here, we are developing an archive and we want your information. What Olivia was saying about how do you convince people that the information about their lives is worth having – and once you have that collection, how do you make it available to everyone – to all the people who may not know what a library means? How do you go out to people – because we are there in those communities also. I’m talking about class… Once you collect, how do you get it out there where people may not be readers? They may not be able to read. And oral histories – how do we make our collections available and protect it at the same time?”

Late though it was, conversations carried on for another half hour! The event fired our archival imaginations at QAMRA, and we carry this spirit of archival comradeship, respect and activism forward.