Queerness at NLS: Whence We Came

24 January 2022

Khushi Khemka and Prajjwal Rathore,

On behalf of NLS Queer Alliance 2021-22.

QAMRA aims to foster discussion about queer rights, and depends on people to voice their opinions to add richness and nuance to conversations. While documenting and preserving histories, an archive’s eternal challenge is to avoid any bias. Therefore, we would like to emphasise that all opinions expressed in this publication belong to the authors alone. QAMRA maintains its neutrality in order to remain a repository of all queer histories.

Buses full of students leave the National Law School of India University (NLSIU) frequently for several reasons. On 19 December, we were on our way not to a conference, match, or co-curricular activity, but to the Namma Pride 2021 Parade. A hundred enthusiastic students with beautiful dresses, bright nail paint, bold make-up and face paint were crammed into two buses. We were the biggest contingent from any institution, a volunteer commented. Although it does go back a long way, engagement with queer rights on the NLSIU campus has not always been like this.

Initially, the discourse on queer rights in India was articulated through medical law jurisprudence. Archival material from the Queer Archive for Memory Reflection and Activism (QAMRA) reveals the participation of professors from NLSIU in such events. On 2 March 1996, Prof. S.V. Joga Rao and Prof. D.K. Sampath contributed to ‘Legal Issues in the Prevention and Care of HIV/AIDS’, a conference organised by NIMHANS. However, queer perspectives were not discussed at the conference in any major way. This would change because of a small group of students.

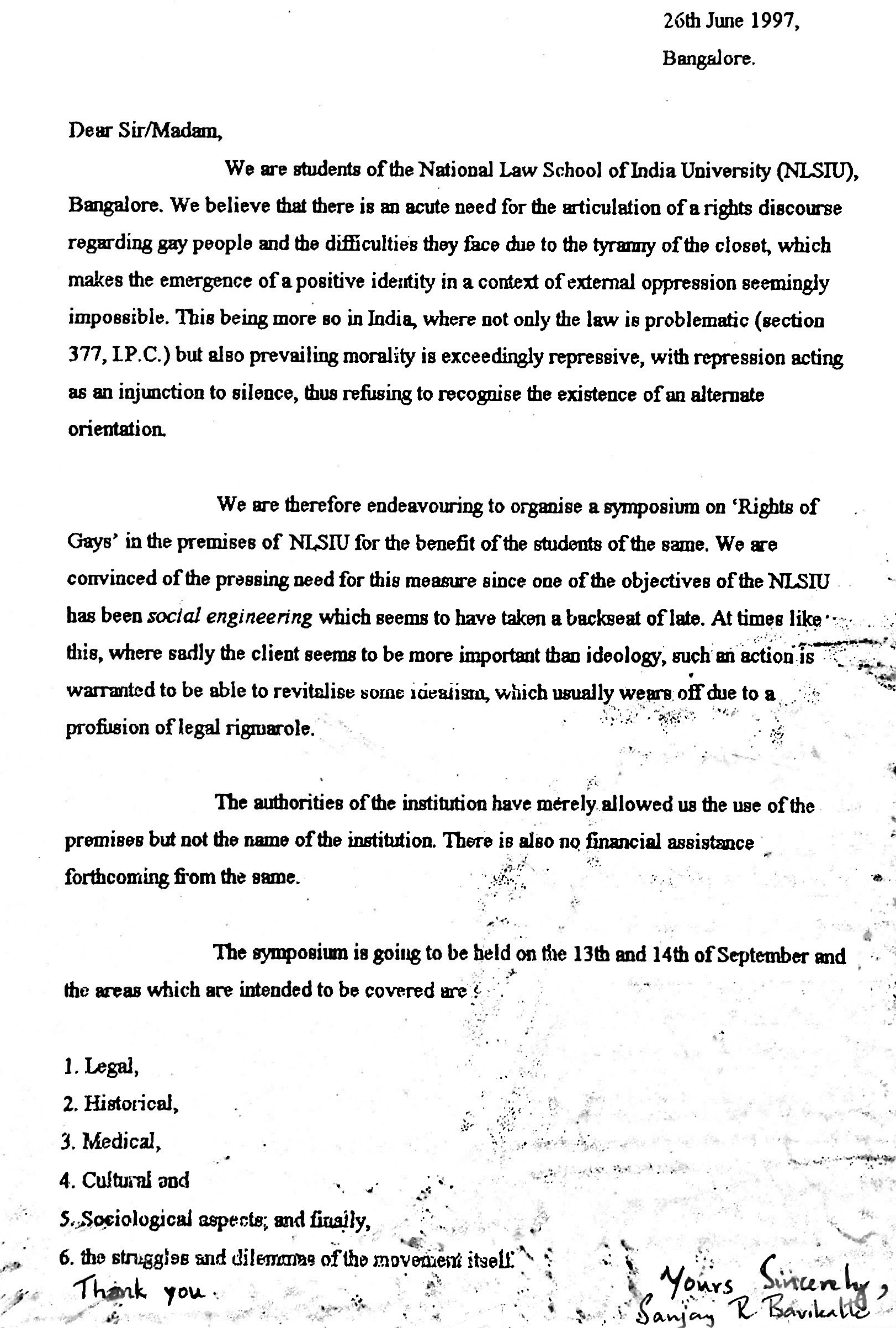

Inspired by Justice Michael Kirby’s talk (Former Judge, Australian High Court), some students at NLSIU worked towards organising India’s first Gay Rights Symposium in 1997. Alumni Arvind Narrain and Sanjay Bavikatte trace back their individual involvement with the movement to this Symposium. If one were to consider the attitude of the University administration towards queer rights discourse as congenial today, it was definitely not so back then. Narrain and Bavikatte recall how the administration provided them space to conduct the seminar, but did not wish to associate with it in any institutional capacity. This reluctance would prove to be of very little consequence. The seminar was received quite well. It was widely covered and is considered to have brought the ‘gay rights’ discourse into the limelight. Finally, the discussion on sexuality started moving from the hush-hush tones of subtext in conferences to proper theorisation. The change was evident soon when NLSIU hosted the consultation conference on HIV/AIDS-related legal and ethical issues in December 1999. In this conference, organised by the Institute on Law and Ethics in Medicine, students and scholars examined HIV/AIDS through the lens of sexuality and gender as well.

Now, almost 25 years after the watershed 1997 conference, queer rights discourse on campus has matured. It has matured in terms of inclusivity, as the conversation has moved from a gay-lesbian paradigm to a more inclusive and fluid one. The painting of a mural that is representative of multiple queer identities, outside the first-year classroom, by trans artists of the Aravani Art Project, along with the NLS Queer Alliance and other students is an example of this maturity. Another indication would be the ‘Gender and Sexual Minority Anti-Discrimination Code’, an official policy on queer inclusivity on campus, which is currently in the final stage of being drafted by the NLS Queer Alliance.

The increased maturity is also in terms of the administration’s involvement and amenability, as evidenced by their engagement with and support of the many queer-issues-related events organised by the students. Now, the University offers seminars on queer subjects by queer faculty. There is also the recent move of QAMRA to the Sri Narayan Rao Melgiri Memorial National Law Library. All of this seems an evolution of NLSIU’s long association with the queer rights movement.

Between the spaces of these hallmark events, everyday realities of queer students at NLSIU are contrarily complicated experiences of liberation and discrimination, both subtle and overt. While the University provides a space for many students to explore their identities, an underlying queerphobia taints our environment. Offensive jokes and slurs are still passed around, not publicly but definitely privately. Some students, after coming out, have noted a change in others’ behaviour towards them, and sometimes, their platonic compliments were perceived in the wrong way. With rare exceptions, heteronormative assumptions and beliefs are still largely prevalent. While there are some courses which apply queer frameworks, queerness remains largely separated from general academic teaching in classrooms. Most courses do not integrate it and if they do, it is very cursory and superficial. There have also been instances of faculty being queerphobic. All this shows that the positive changes at NLSIU come with big qualifiers.

This begs the question: where do we go from here? While judgements like NALSA (2014) and Navtej Johar (2018) have helped open conversations, especially in the legal realm, they are not the answer to every issue; the onus is upon us to create a safe space for queer people. The campus needs to work towards continuous sensitisation with the one takeaway being—there is still a long way to go.